Going with the flow.

This is another piece on how air sourced heat pumps (ASHP) work…

Oh no, can’t we talk about anything else?

Not yet, and bear with me. This is a fundamental thing to consider when trying to get the most out of your pump. But it helps to understand how a heat pump works to get understand why this makes such a big difference.

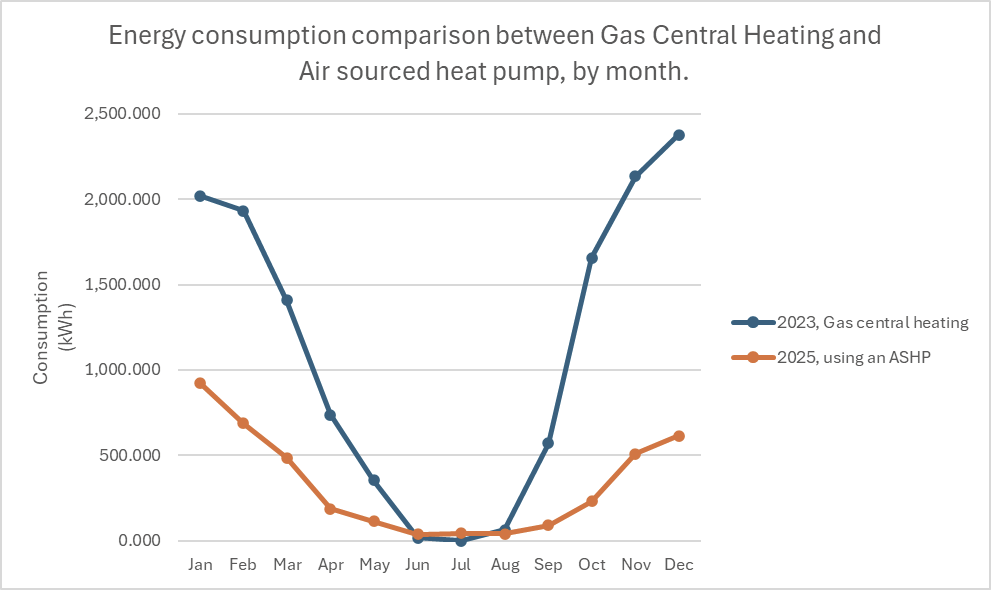

Fundamentally, a heat pump, like an air conditioning unit or fridge, uses a compressor to pull heat out of the air they draw in through the fan. ASHP use the principle of heat dynamics and some chemicals that have a low boiling point, that allows it to transfer as much heat out of the air as is possible, into the compressor. This squeezes the gas, generating high levels of heat which is conducted to the heating coils, which heat the water going to the radiators or the hot water tank.

This is why ASHP are so efficient compared to a fan heater or immersion heater, that squeezing effect can be thought of as a multiplier for the heat “pulled” out of the air. The chemical in our pump is propane, and it’s boiling point is -42°C, so basically, our heat pump works well even if the outside temperatures would kill a mammal like us.

The heat pump does have a back up plan, for when the “flow temperature” being generated is lower than the one needed to heat your water or rooms, there is a back up electrical heater.

Which is the point of this post.

Finally! Which is what, please?

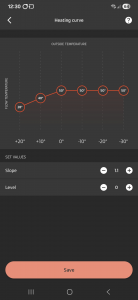

When the ASHP was installed, it was given some settings to describe how it should behave.

For the summer, the maximum flow rate (or the maximum temperature coming off the compressor) was set to 50°C, which would work well for us, if we weren’t trying to use our house as a heat store.

We bake the house at midday and, fundamentally, only heat our hot water once a day. As we have solar cells, our time of day is midday’ish – I shift the time based on our house’s solar elevation (I talk about solar elevation on 14th February 2026).

What?

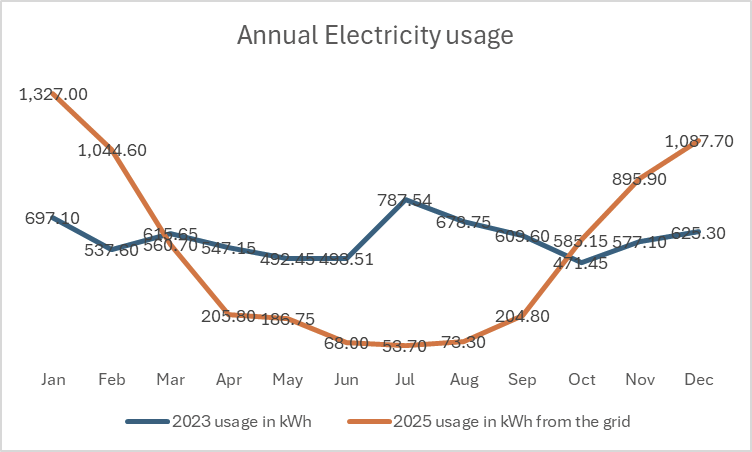

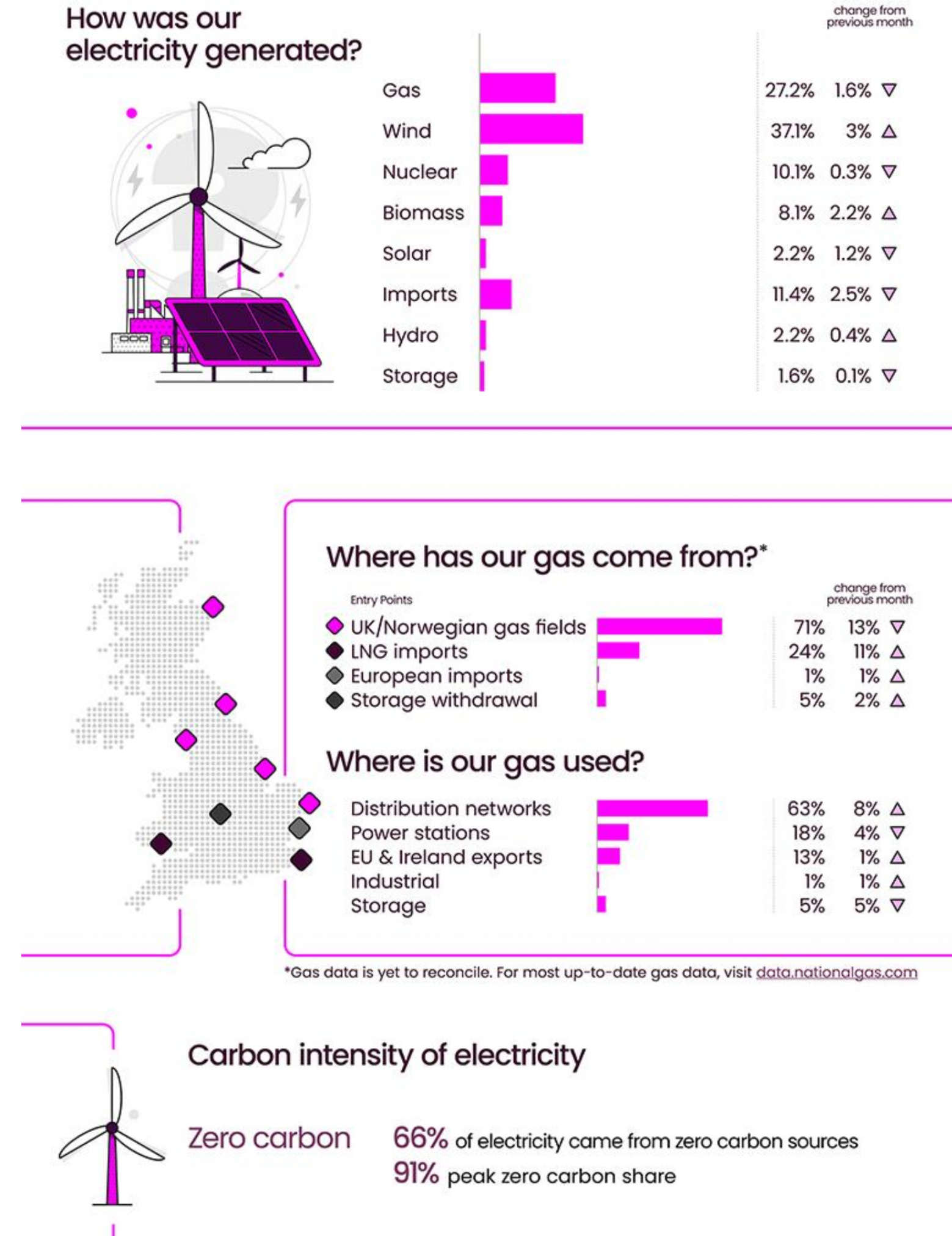

We get free solar engergy off our roof (well not free to install, but we bought the panels many moons ago, so it is free now). Plus, our solar energy is definitely carbon free (their carbon debt being paid off back in 2016, please see Number Crunching Part 1). Making the most of that energy is really important to us for those very reasons – keep our costs down and our CO2 emissions to a minimum.

OK, I’ll bite, is this your only option?

We could sell that back to the grid and then buy back energy later in the day. But our rates don’t change: Ovo’s Simpler Energy Plan has a low standing charge, so while the units are a little higher than other plans in Ovo’s range, we benefit during the summer when we’re effectively off-grid.

Which all means that our heat pump is not working for us as well as it could for these reasons.

Why is that?

The coefficient of performance (COP) for our heat pump is around 4.1 per annum, that means for every kilowatt hour of energy it consumes, it produces four point one kilowatts of heating. Basically 1kWh = 4.1kWh. That’s made of the electrical heater and the compressor.

The electrical heater has a lower COP, about 1. Our best strategy is not to use the heater unless necessary.

Yet, when I looked at the figures that was exactly what was happening! So far (today is the 24th January), we’ve used 734kWh in the compressor and 50.4kWh from the heater. Why?

Well, the heat pump has a setting called “maximum flow temperature”, which has a little leeway, but it states how much of the flow temperature comes from the compressor. Ours, like many set in the UK, was set to 50°C. Everytime we try to heat our hot water up to 55°C once a day, the electrical heater was being activated. For at least £13.10 worth of electricity, that we shouldn’t need!

So, I’ve set the maximum flow rate to 57°C. This should allow us to get to our 55°C easily without needing to turn on the heater. We could set the max flow temperature all the way up to 65°C, but that might get the compressor over exerting itself at times, and I don’t mind a fiver or so spent to keep everything working well.

Is it really going to make that much of a difference?

Let’s look at last year, if you remember, we can have a look at the way our heat pump used the energy it consummed.

| Total in kWh | Compressor in kWh | Electrical Heater in kWh | Heat generated in kWh | |

| Nov 2024 | 544 | 509 | 34.5 | 2,330 |

| Dec 2024 | 603 | 585 | 18.5 | 2,640 |

| Jan 2025 | 926 | 863 | 62.5 | 3,390 |

| Feb 2025 | 686 | 653 | 32.7 | 2,720 |

| Mar 2025 | 486 | 463 | 22.9 | 2,010 |

| Apr 2025 | 187 | 183 | 4.5 | 1,010 |

| Jun 2025 | 113 | 111 | 02.0 | 632 |

| Jul 2025 | 38.1 | 37.8 | 0.3 | 220 |

| Aug 2025 | 43 | 42 | 1 | 222 |

| Sep 2025 | 90.7 | 88.9 | 1.8 | 537 |

| Oct 2025 | 231 | 227 | 3.7 | 1,240 |

| Nov 2025 | 510 | 493 | 16.7 | 2,130 |

| Dec 2025 | 617 | 597 | 18.4 | 2,600 |

| Jan 2026 | 1,000 | 940 | 62.5 | 3,440 |

| Feb 2026 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Mar 2026 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Apr 2026 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Total | 6,074.8 | 5792.7 | 282 | 25,121 |

This is something we’re going to try until April, I will let you know how it goes, probably with a graph.

If we can reduce the power used, because the compressor is more efficient than the heater, it’s probably something we’re going to keep doing!

Is it worth it to save 122.6kWh between January 2026 and April 2026?

From a money point of view that’s 122.6*£0.26 ~ £31.88. Is it worth the squeeze? But if we can reduce our CO2 levels further, it’s got to be worth it, hasn’t it?

Posted: January 31st, 2026 under Driving off the grid.

Comments: none