What is happening with the weather?

Strolling through our local town centre or talking with family, it’s tempting to think that the grey skies overhead this UK winter are a sign that climate warming isn’t really happening.

Actually, they are almost certainly a symptom of climate warming in action. Compared to the past few Novembers, November 2025 was dramatically warmer and wetter. In our little bit of the world, temperatures were in the low to mid teens Celsius (55-62°F) for the first half of the month. Even when they dropped, between the 19th and 21st November, they rarely dropped much below freezing for long. Typically, in November, the nights stayed around 5.8°C.

Rainfall was significantly heavier in November 2025, nearly 1.5 times as much as expected. That might sound like good news as we’ve had very dry summers, but as we enter the second week of February 2026, the rain hasn’t stopped in some parts of the UK for 35 days.

November was a bit sunnier (despite the wet weather) too.

December 2025 was cooler towards the end but had a warm day on the 9th December of 12.5°C, a whole 7°C warmer than usual. It was drier but when the cold weather came in, another Artic blast like November, starting over the Christmas period. No, that didn’t bring snow.

January 2026, was cold. 0.5°C less than the average temperatures. In Marham, Norfolk, temperatures dropped to -12.5°C on the 5th January!

Our part of East Anglia is typically much milder by comparison. One of the benefits to living in the urban sprawl, is the council grits the roads and the sheer number of people keep things that little bit warmer. The towns in the area are typically 1-2°C warmer than the villages as a result.

Bad in the summer, but a blessing in the winter.

2025 was the warmest year on record for the UK, although we lacked the baking days of the summer 2022; 2022 had lower average temperatures though the high extremes were just that.

It’s the averages that matter. The UK benefits from being an island archipelago featuring a large number of inhabited islands: Northern Ireland and England, Wales, and Scotland being the significantly populous ones. It sits within 11 degrees of latitude and 15.5 degrees of longitude, which means what is happening at the south-westerly point is very different to what’s happening in the north-easterly point, weather and climate wise.

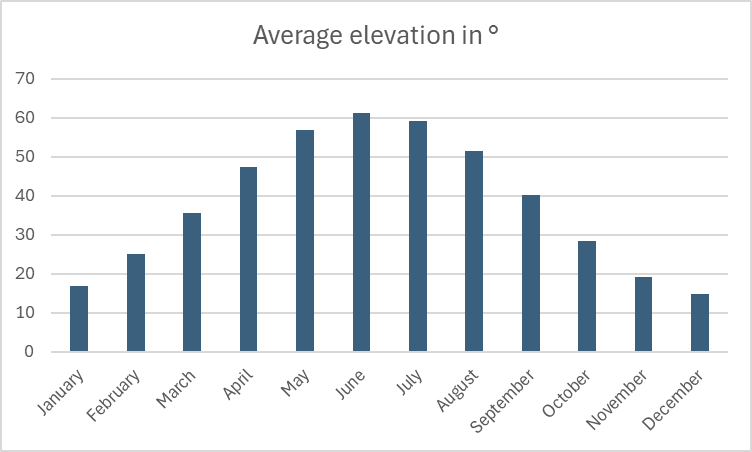

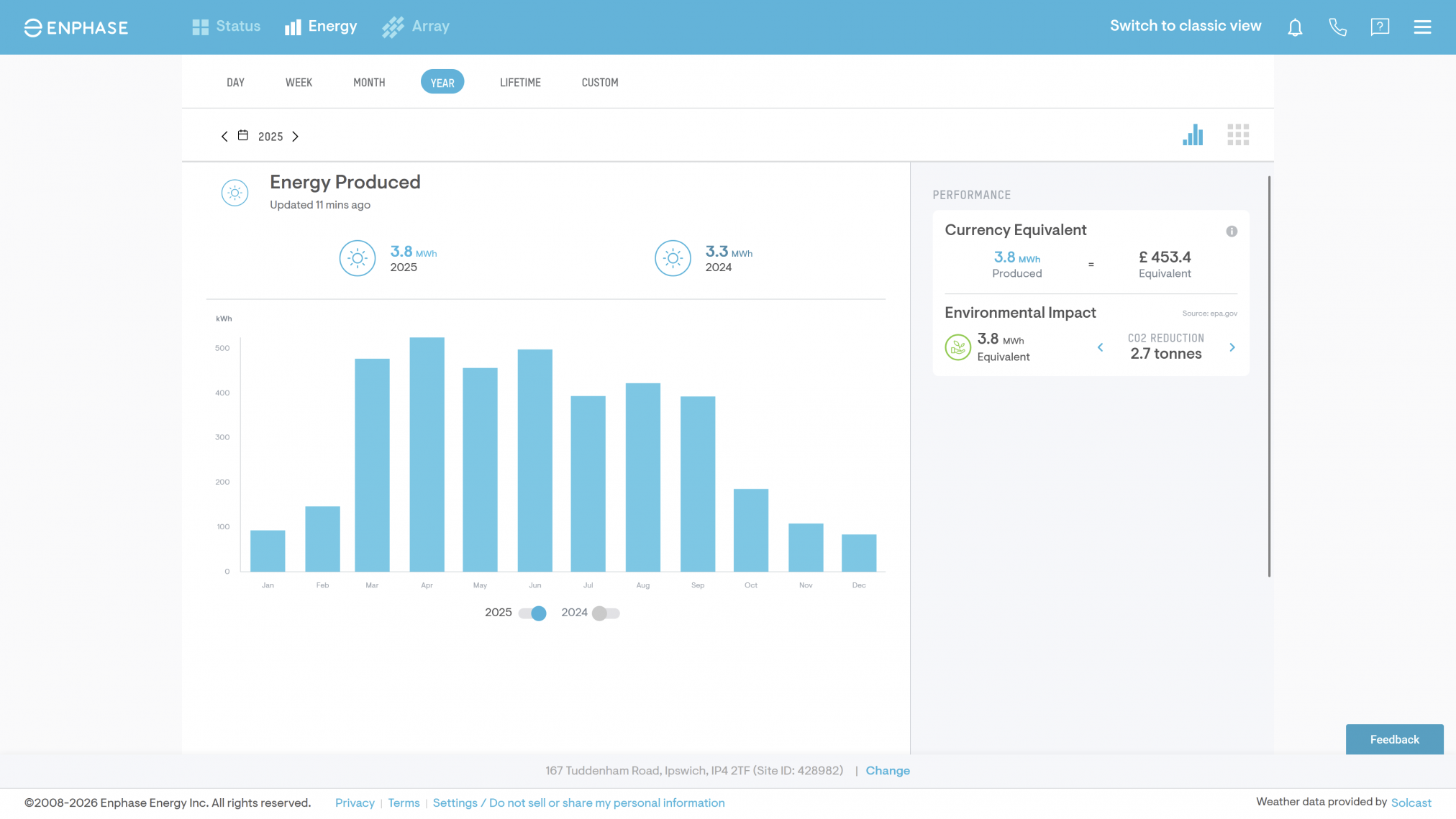

In my area, we benefit from a couple of things: longer days in the summer and winter, making solar panels worthwhile for home generation. We have a coastline, making off-shore wind power accessible at scale. It’s sparsely populated, having been agricultural for a long time, though the plans to build many more homes will change that.

East Anglia is also deemed semi-arid, by UK standards. We get little rainfall. The rain in mainland UK comes from the west. Which suggested the weather late 2025 and 2026 has been dominated by Atlantic weather systems. As lay people call it, specifically, the Gulf Stream.

The Gulf Stream is a current traveling from Mexico, past the USA east coast before bending towards Europe. Mexico is on the Tropic of Cancer, and unlike the Equator, these latitudes are seasonal and typically warmer than the latitudes to the north and south of these boundaries. They have seasons as a result, much like the UK, though milder winters at sea level than a relatively northern island group like the UK.

The UK should be a cold little set of islands in the winter, but the Gulf Stream contributes to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which changes that by bringing milder weather up to us from the Tropic of Cancer. AMOC does this by acting as a conveyor belt: warm salty water flows towards the Artic where it cools and sinks. Colder deep water then flows southwards, completing the circulation. Freshwater from melting ice can reduce salinity and slow this sinking process, weakening the system..

One of the concerns with climate change is that the AMOC depends on differences in water density, driven by both temperature and salinity, to keep it circulating. As the climate warms, increased freshwater from melting ice can reduce salinity in the North Atlantic and weaken this circulation, potentially reducing the amount of heat transported towards the UK.

This is likely because as temperatures rise, more ice melts in the Arctic and around Greenland. This happens naturally each year, but climate change increases the overall amount of freshwater entering the North Atlantic. Ice is made of fresh water, so this added input reduces the salinity of the surrounding sea. Lower salinity makes the water less dense, which means it does not sink as readily in the far North. Because this sinking helps drive the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, reducing it can weaken the system and reduce the amount of heat transported towards the UK.

Posted: February 21st, 2026 under 42, Driving off the grid.

Comments: none