Master of our Ship 🚢.

Transparency Note: This post contains affiliate links to energy partners like OVO (marked with [Ad]). If you click them, I may earn a commission. I am sharing my personal data and journey as a homeowner; please remember that energy performance is highly specific to each property. Individual results will vary [AD].

I’ve obviously had some time recently to get into the nitty gritty of our heating system, tuning the heat pump settings to match the weather conditions. Not the sort of thing that people usually do with their heating.

Up to a point, I have been interested in how it all works, but my driver is to reduce our carbon footprint: which has largely been achieved just by letting things run.

Isn’t that enough? Can we talk about something more interesting, please?

Bear with me, this is interesting to some.

From our figures, the heat pump did save us money without anything more. But, what if it were more marginal than that? What if we had to tighten our belts? How do we do the best that we can? How can we keep the heat pump running as long as it should do (with proper servicing)?

I have to say, the window figures and their payback were a bit of a shock. I am sitting here with it 4°C outside, feeling very cozy and having spent only 10.6 kWh to feel that since midnight (overnight it dipped to 2°C). The heat pump buzzed along happily, ramping up for when we got out of bed.

Air sourced heat pumps (ASHP) are very different to gas boilers, as heat pumps like “humming along”, having periods where they can flex up and gently ramp back down. Gas boilers are a bit happier to just switch on and off as required. To save money, switch the gas boiler off for a bit, let things cool down then heat them back up when you want more heat.

ASHP efficiency is all about the ambient air temperature. We’ve positioned ours to take advantage of the morning sun, which helps take the edge off the frost in the air around the pump. More importantly, we’ve tucked it into a sheltered spot to protect it from the prevailing south-westerly winds and the infamous East Anglian ‘lazy wind.’ By blocking these winds, we reduce ‘wind-chill’ on the unit, which prevents the pump from having to work harder or entering its defrost cycle more often than necessary.

Heat pumps work by extracting heat from the air they draw in, so when the wind is blowing directly into it, it struggles to pull out as much heat. Think of blowing on the skin on the back of your hand, that air is colder than the surrounding air because it is being forced directly on to your skin – this is a similar principle.

Tuning the heating curve.

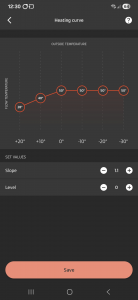

The other thing I’ve started doing with the heat pump is changing its “heating curve”. This is the temperature it tries to get the “flow temperature” coming out of the pump for any given input temperature.

If we had underfloor heating everywhere, a heating curve of 0.7 would likely to be a perfect heat curve when teamed with the Tado™ smart room thermostats and smart TRVs on the radiators. Unfortunately, our upstairs circuits are all radiators, and some aren’t really big enough for the rooms they are in (we have plans to swap them out in the summer). So, on a warmer day, like today, I find that setting the curve to be 0.8 works for us. During colder days, we find a heating curve of 1.1 is more suitable to keep us comfortable.

The heating curves we’ve used over the past seven days.

The heating curve sets the water going into the underfloor heating pipes and the radiators. At warmer temperatures, the heat pump sends cooler water to these pipes as it doesn’t need to bring the rooms up to temperature in the same way, it is not fighting the temperature against the thermostats but working with the environment.

So, why not just set the curve to 1.1 and leave it there? Well, if we did that, we’d use much more energy and it wouldn’t allow the heat pump to coast when everything is a bit warmer. At the moment, having switched it from 0.9 last night to cope with a drop to 2°C, we had the pump coming on earler and harder over night, but is now gently working, keeping everything warm without much effort.

We do not allow the house to get cold, even when it is resting, the pump is running very gently. As I’m typing this at noon, the pump is pre-heating the house for when the sunsets. We’ll run this way until April, when the batteries from our solar generation will start to earn their keep again. Last year, we spent very little on electricity for our heating and hot water between March and September. Over the summer itself, between June and August, I will turn off the heating circuit completely as I did last year.

What about when you leave the house?

Well, unless we’re away for a number of days, it is not worth switching off for a few hours. Allowing the house to get cold does not save us money. Indeed, I am using the house as a thermal store for our energy.

So it’s a different way of looking at the seasonal problem, in the UK?

Pretty much. And so much cheaper, in terms of power used, than the gas boiler. Remember, the best we ever did was 12.9 MWh for the gas boiler compared to 3.9 MWh for the year with the heat pump. And that was before we started actively tuning what we were using.

When we had the pump installed, we were told to “set it to 32°C and enjoy”. We’ve running it between 21°C and 25°C (which mirrors our rooms thermostat settings) against variable heat curves. We’re more than enjoying it.

Posted: January 24th, 2026 under Driving off the grid.